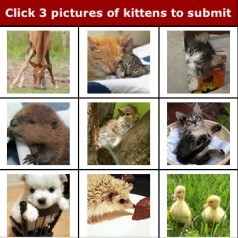

How often do you encounter an image captcha when logging into a website? I probably meet one or two a week, instructing me to “click all squares with shop fronts”, “click all squares with signs” or something similar. They’re a bit annoying – another step to accessing what I want – but they’re just there for our protection, right? To prove that we’re human, not bots, right?

Well, yes, but there are many ways to do that. The real reason we’re being asked to identify images is that we are training AI for Google and other big tech companies. In the days when captchas were semi-legible bits of text, Google was busy digitising books and articles, and we were unknowingly helping them to verify difficult-to-read words. Today the current task is training AI to recognise images – for example driverless cars need to recognise road signs. Instead of employing people to enter and verify data, we’re doing the job for free. Yes, we’re also proving that we’re human, but at the same time we’re helping military drones recognise the people they are programmed to kill.

Francis Hunger’s chapter “How to Hack Artificial Intelligence” in “State Machines – reflections and actions at the edge of digital citizenship, finance and art” brought my attention to this side of seemingly innocent captchas and other AI learning activities that we participate in on a daily basis. Hunger presents a selection of art projects that playfully or seriously investigate the possibilities of interfering with machine learning and AI systems – from hairstyles, make-up and clothing that disrupt facial recognition to a magic circle of road markings capable of trapping a driverless car. These projects draw attention to the numerous failings of AI and offer civil disobedience tools that will no doubt be increasingly useful in this age of digital tracking and surveillance.

Hunger concludes with a nod towards the invisible work involved in training AI, quoting the artist Sebastian Schmeig who suggests that the ultimate goal of AI is not only to do work that humans could do, but to make this labour invisible – and therefore more easily underpaid or unpaid (where humans might actually still be doing it). A growing body of research and artwork explores this area, including the Data Workers Union – an “international organisation seeking to pursue data labour rights as citizens of a datafied society”. They argue that the data we collectively produce is a resource being extracted by big tech companies for vast profits, calling data the new oil, and demand ownership of the data, payment in exchange for its use and an end to digital colonisation.

It brings to mind my recent experiences in Sweden and Denmark, where I was unable to purchase food with cash. Only cards were accepted. As digitisation is forced apon us, by governments acting in cooperation with finance and tech corporations, it’s essential that we maintain a critical attitude and constantly question the motives behind every action, be it image captchas for “our security” or digitised finances for “our convenience”.