| |

Magdalena Sin Fronteras

Santa Clara, Cuba, January 2008

Cuba: land of Che and Fidel, of cigars and old cars, tiny thorn in the

great flank of western capitalism. And home to Estudio Teatral in Santa

Clara, organisers of Magdalena

Sin Fronteras, a festival gathering of

the Magdalena

Project.

They invited me to come to the festival. I asked Creative

New Zealand for the airfare and, to my surprise and delight, they

said yes.

Cuba

is not an easy place to get to; organising my travel took a ridiculous

amount of time, so I decided that if I was going to go to all of this

effort, I needed to see more than the festival. What are my chances of

getting to Cuba again? I planned two days in Havana before the festival,

and a week afterwards, wherever I might end up. Cuba

is not an easy place to get to; organising my travel took a ridiculous

amount of time, so I decided that if I was going to go to all of this

effort, I needed to see more than the festival. What are my chances of

getting to Cuba again? I planned two days in Havana before the festival,

and a week afterwards, wherever I might end up.

I didn't have much time to prepare; my Spanish was minimal and rusty,

and most of what I knew about Cuba came from a few movies such as "How

Cuba Survived Peak Oil" and "Before

Night Falls". I understood a potted history of the revolution

and the consequences of the USA blockade, and I browsed Wikipedia.

I searched the internet for signs of alternative Cuba, of net.artists

or digital artists based in Cuba ... but found none.

And then I was there: standing at immigration and wondering whether

the three errors in my visa (involving my surname, date of birth and

nationality) were going to cause a problem. Wondering whether anyone

from the festival would be there to meet me, given that my flight was

an hour late and immigration was taking ages. But nobody minded

about the discrepancies between my visa and my passport, and on the other

side Maria from the National Association of Theatres and her son were

patiently waiting for me. They delivered me to a casa

paticulare (private house with guest rooms) where Jill Greenhalgh

and Gilly Adams had arrived the day before.

We had two days to check out Havana before the festival bus would take

us to Santa Clara.

Havana

is a bustling city, but a bustle that involves no advertising

and much less traffic than most cities of similar size (population 3

million). And much more diverse traffic as well - gleaming

late model cars share the roads with dusty truck-buses, battered taxis,

beautiful old classics, bici-taxis and various horse-drawn conveyances.

Sacks are hung from the horses' rear ends to the front of vehicle

towed to catch what would otherwise render streets a stinking

mess. The streets are clean but pot-holed, the pavements are broken and

the buildings grand but mostly in poor repair - especially the hurricane-lashed

buildings on the water-front Malecon. And everywhere

there is graffiti - political slogans, billboards extolling the virtues

of the revolution and huge images of Che (and occasionally Fidel or Camillo,

but Che is obviously the best-looking). Havana

is a bustling city, but a bustle that involves no advertising

and much less traffic than most cities of similar size (population 3

million). And much more diverse traffic as well - gleaming

late model cars share the roads with dusty truck-buses, battered taxis,

beautiful old classics, bici-taxis and various horse-drawn conveyances.

Sacks are hung from the horses' rear ends to the front of vehicle

towed to catch what would otherwise render streets a stinking

mess. The streets are clean but pot-holed, the pavements are broken and

the buildings grand but mostly in poor repair - especially the hurricane-lashed

buildings on the water-front Malecon. And everywhere

there is graffiti - political slogans, billboards extolling the virtues

of the revolution and huge images of Che (and occasionally Fidel or Camillo,

but Che is obviously the best-looking).

After playing tourists in Havana, we escape for a day to the beaches

east of the city. Our driver and guide, Umberto, is an engineer but

he works as a taxi driver because the pay is better, due to the possibility

of getting tips in convertibles. Cuba operates a dual currency system:

Cuban pesos for Cubans, and Cuban convertible pesos, worth 24 Cuban pesos,

for tourists. At first the system seems bizarre and unfair, but there

is a logic to it: the redistribution of wealth.

And we visiting theatre artists are wealthy, in comparison to Cubans

whose salaries are the equivalent of about 10 to 20 US dollars a month.

Everyone has a job, housing, free health care, free education, and basic

food. But certain things, including petrol, many food items and most

"luxuries", can only be purchased with convertibles, making

it necessary for Cubans to operate in both economies if they aspire to

anything above the most basic standard of living. One exception is books,

which are incredibly cheap and sold in Cuban pesos - unless you chose

to shop at the over-priced outdoor book market in the touristic old town.

Step into a local bookstore and, as long as you read Spanish, you have

a wide selection of very affordable books.

The day for the festival to begin arrived, and a big yellow guagua (pronounced

"wah wah" - South American Spanish for bus) pulled up outside

our casa near enough to 8.30am for us to think the day was beginning

well. There was much delight as we were reunited with other Magdalenas

from different corners or the globe. Off we set - but two hours later

we still had not left the city; in fact we were almost back where we

started. Someone had forgotten a bag, then someone had to go to the toilet,

someone needed a cigarette, someone else needed to go to the toilet,

someone wanted coffee ... finally close to 11am the bus headed past various

national monuments for the second time and then out onto the Autopista,

bound for Santa Clara.

This

was the second festival organised by Roxana Piñeda

and her theatre company, Estudio Teatral de Santa Clara (the first

was in 2005). The programme featured about 20 performances, half

Cuban and half international, as well as workshops and forums. The opening

of the festival took place that evening in the town square, and featured

performances by a large number of young performing arts students - Afro-Cuban

dance followed by an all-male contemporary dance performance. It seemed

that the whole town had turned out for the opening, and throughtout the

festival there were consistently full houses. This

was the second festival organised by Roxana Piñeda

and her theatre company, Estudio Teatral de Santa Clara (the first

was in 2005). The programme featured about 20 performances, half

Cuban and half international, as well as workshops and forums. The opening

of the festival took place that evening in the town square, and featured

performances by a large number of young performing arts students - Afro-Cuban

dance followed by an all-male contemporary dance performance. It seemed

that the whole town had turned out for the opening, and throughtout the

festival there were consistently full houses.

We surrendered to festival mode - days full of workshops and forums,

evenings full of performances. I joined a dramaturgy workshop led by

Gilly Adams (Wales), which became more of a cultural exchange as the

group was roughly half European women and half Cuban

men, with one female Cuban participant, one Colombian man, and our translator

- who in her first year of study to be an interpreter. This was her

first work experience - a big challenge, as we were writing creatively

with lashings of metaphor, poetry, word play and irony. There was also

Antipodean me, and Luciana Bazzo, from Brasil but living in Denmark.

Through the exercises that Gilly set for us, we uncovered delicious details

about each other and our varied backgrounds and cultures. In just three

mornings, we had a very rich sharing.

Every evening there were at least two

performances. One night we were taken to Mejunje,

the closest thing to an underground venue that I experienced in

Cuba. Contained within the walls of a long-gone building, open to the

sky and incorporating trees amongst the seating, Mejunje has earned a

reputation as an excellent alternative music and performance venue. The

owner made a speech, welcoming the Magdalena festival delegates, and

for some reason that my limited Spanish prevented me from understanding,

he presented a painting to another man. Then the show began - a solo

performance from Havana-based Estudio Vivarta. i was amazed to realise

that it was about Katherine

Mansfield. How strange to be sitting in an open-air theatre in Cuba

watching a performance about one of New Zealand's most internationally

famous writers. Later I spoke to the performer, who told me that she

had taken over the role from another performer who had left the company,

so she couldn't tell me why they had chosen to make a show about

Mansfield. It was a very physical piece, packed with imagery, anger and

energy - it would be great to bring to New Zealand.

There

were forums every afternoon, during which different directors and

performers spoke about their personal theatrical journeys. Like the performances,

these were incredibly well attended - usually standing room only - with

high school students as well as local artists and academics. I was struck

by the contrast - how we struggle to get audiences for this kind of thing

at home, yet here people are hungry for theatre, for discussion, for

exchange. There are different priorities, different paces of life. There

were forums every afternoon, during which different directors and

performers spoke about their personal theatrical journeys. Like the performances,

these were incredibly well attended - usually standing room only - with

high school students as well as local artists and academics. I was struck

by the contrast - how we struggle to get audiences for this kind of thing

at home, yet here people are hungry for theatre, for discussion, for

exchange. There are different priorities, different paces of life.

My main role at this festival was to participate in the

second Women With Big Eyes collaboration; nine of us had

worked together at Transit

V in Denmark in January 2007, and a year later in Cuba there

were eight of the original group plus a few more joining in. Unfortunately

the festival programme only gave us three mornings to work and a presentation

slot, and because every day at least one person from the group was giving

a performance or work demonstration, we had a somewhat interrupted process.

But some of us were able to spend an extra afternoon experimenting with

the data projector and flexible mirror, and in the end we presented a work

of  about

15 minutes that incorporated video and other elements from the previous

iteration with new material, some new people and new ideas. Once again,

the presentation proved to be very moving and rich for the audience.

What is interesting to me is that we have taken a story as a starting

point, deconstructed it, then fed in the things that each of us felt

important to bring to the work - and created something that the audience

can each individually read something in. It must be a combination of

the experience of everyone in the group along with the pressure-cooker

working method - there is no time to deeply explore, decisions must be

made quickly on instinct and practicality. And the result is powerful. about

15 minutes that incorporated video and other elements from the previous

iteration with new material, some new people and new ideas. Once again,

the presentation proved to be very moving and rich for the audience.

What is interesting to me is that we have taken a story as a starting

point, deconstructed it, then fed in the things that each of us felt

important to bring to the work - and created something that the audience

can each individually read something in. It must be a combination of

the experience of everyone in the group along with the pressure-cooker

working method - there is no time to deeply explore, decisions must be

made quickly on instinct and practicality. And the result is powerful.

As always, the networking and meeting with other like-minded

people from around the world is what makes Magdalena festivals such vital

experiences. It was wonderful to catch up with those I already knew

- I was staying at the same place as Jill, Gilly, Julia Varley, Geddy

Aniksdal and Lars Vik, Dah Theatre (Dijana Milošević, Maja Mitić and

Sanja Krsmanović Tasić) and Cristina Castrillo and Bruna Gusberti, which

was very nice and familar - and there were several others there I knew

from previous festivals. I made new connections with Elizabeth de Roza

(Singapore), Letícia

Castilho (Brazil) and many others, although not being able to speak Spanish

was really frustrating (if I could do anything different in my life,

I would learn as many languages as possible, from birth!). At the final

round when we were all asked to make one wish, I said yo

deseo hablar y entiendar español; so

now I really must learn it!

Ten

days of watching performances mostly in Spanish, struggling to catch

English translations of announcements at the end of the performances,

trying to order food and drinks in Spanish (actually the drinks are

easy) AND trying to take in all of the content of the workshops,

forums and performances, pushes one towards exhaustion. But moments of

unexpected beauty are the perfect antedote for exhaustion. One day we

visited the jubiladas (elderly women) in the casa

de las anciens (house for the ancients) next door to the theatre.

Roxana and her company are regular visitors, singing songs with their

neighbours, and many of the elderly women stood up to perform their own

special numbers. At the far end of the courtyard sat a chair-ridden old

woman who, when the music stirred her, waved her fist in the air and

cried, "Viva

Fidel!" Ten

days of watching performances mostly in Spanish, struggling to catch

English translations of announcements at the end of the performances,

trying to order food and drinks in Spanish (actually the drinks are

easy) AND trying to take in all of the content of the workshops,

forums and performances, pushes one towards exhaustion. But moments of

unexpected beauty are the perfect antedote for exhaustion. One day we

visited the jubiladas (elderly women) in the casa

de las anciens (house for the ancients) next door to the theatre.

Roxana and her company are regular visitors, singing songs with their

neighbours, and many of the elderly women stood up to perform their own

special numbers. At the far end of the courtyard sat a chair-ridden old

woman who, when the music stirred her, waved her fist in the air and

cried, "Viva

Fidel!"

I was disappointed not to be able to attend another performance

at Mejunje late one evening, outside the festival programme.

Mama tiene leche (Mama has milk) had such a long and bizarre

description on its flyer - translated for me with much laughter and disbelief

by the wonderful Alejandro - that I was completely intrigued. The word

that initially grabbed my attention was "ciberamazona" but

the blurb went on to mention Dracula, Godiva, pop art, digital games,

and so many other influences that it had to be something incredible -

either incredibly good or incredibly bad. Alas, our dependency on the guagua to

get back to our accommodation meant it was difficult to fit in extra-festival

late night events - even a mojito after the shows had to be a quick one.

So I will have to wonder forever about Mama tiene leche.

Gabriella

and I did break out one day, with Maikel from our writing workshop, who

took us up into the Escambray region via the extremes of transport: first

an expensive taxi, then the extremely cheap, dusty and rattling local

bus and at the end of the day we came back down to Santa Clara in the

car of friends of Maikel, complete with 1980s music and strong local

spirits passed round in a bottle. We visited Teatro Escambray, once the

foremost theatre in Cuba, which has a farm-like establishment near Manicaragua.

The company members live and work here (Maikel has a room as he is a

writer with the company), but as they were on their rest period that

week only about 10 people were around. There are about 25 artists in

the company and more than as many again who are workers (technicians,

set builders, etc). From the theatre we collected Maikel's

friend Gorge and went to Lake Hanabanilla, a man-made hydro dam lake

of considerable beauty. Maikel and Gorge hired a rowing boat and we set

out across the lake to swim and explore its distant shores. Gabriella

and I did break out one day, with Maikel from our writing workshop, who

took us up into the Escambray region via the extremes of transport: first

an expensive taxi, then the extremely cheap, dusty and rattling local

bus and at the end of the day we came back down to Santa Clara in the

car of friends of Maikel, complete with 1980s music and strong local

spirits passed round in a bottle. We visited Teatro Escambray, once the

foremost theatre in Cuba, which has a farm-like establishment near Manicaragua.

The company members live and work here (Maikel has a room as he is a

writer with the company), but as they were on their rest period that

week only about 10 people were around. There are about 25 artists in

the company and more than as many again who are workers (technicians,

set builders, etc). From the theatre we collected Maikel's

friend Gorge and went to Lake Hanabanilla, a man-made hydro dam lake

of considerable beauty. Maikel and Gorge hired a rowing boat and we set

out across the lake to swim and explore its distant shores.

Simply being in Cuba was a fascinating

experience. Despite problems such as the great lack of technical

resources, the excess of governmental control over people's lives and

(most shocking to me) the impossibility to have the internet at home,

there were many positive things. We visited a performing arts school

where 15-18 year olds learned dance, music and theatre along with regular

school subjects; on graduation, they are guaranteed a job in their art

form. Employment is almost 100%,

as is literacy. Health care and education are free. Crime is low and

there are very little drug-related problems. It doesn't make sense to

compare it with capitalism because the pros and cons are so different,

but it's good to know that an alternative, imperfect as it may be, can

and does exist. Even now that Fidel has made the sensible move of bowing

out before he's carried out, rapid change in Cuba seems unlikely. The

Cuban people want some changes but they're in no hurry to give away

the good things the revolution has given them.

Having seen "How

Cuba Survived Peak Oil" (documenting the "special period" when

the Soviet Union collapsed and Cuba's oil supply was cut off almost

overnight) I was interested to see how today's reality compared to

the idealism of the film. Many Cubans referred to the period especiale but

the USA's trade embargo (in force since 1962) was more often

blamed for the chronic shortages and other problems. I didn't see any

of the urban community gardens that the film describes, but in the

countryside and the edges of small towns there were many well-tended

market gardens.

Everything is organic, so nothing is advertised as organic (nothing

is advertised, fullstop). Cuban cuisine - especially for vegetarians

- is not remarkable; sometimes a change from rice and beans would be

nice. But the coffee, mojitos, peso pizza, peanuts and fruit are

all good.

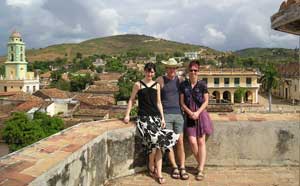

As

the festival ended, I took a bus to Trindad with Zoe and Simon from Ireland.

Not the Trinidad-and-Tobago Trinidad, but a small town in the south of

Cuba, recently made a UNESCO world heritage site and apparently the second

stop for tourists after Havana. Known for its music houses, Trinidad

is very quaint with cobblestoned streets, prettily painted houses lining

the streets, a great swimming beach nearby and a lush valley behind.

Now was the time for sleeping, wandering, stumbling around the dance

floor with the very patient local men, enjoying the luxury of toilet

seats (which are scarce in Santa Clara) and floating on my back in the

Carribean without anything in particular to do. Bliss!

We

met Mercedes Borga and Montimar,

the music group she manages,

and visited her home where her partner Coki gave us a lesson in ceramics.

We took a tourist train into the Valle

de los ingenios and I climbed

the tower at Manaca Iznaga - a huge structure built a couple of centuries

ago by the local oligarch to keep an eye on his slaves in the fields.

I spent quite a lot of time lying on the sand or my bed or drinking mojitos

or beer and reading the guide book, filling in a little bit of the vast

gaps in my knowledge of the history of the country. We

met Mercedes Borga and Montimar,

the music group she manages,

and visited her home where her partner Coki gave us a lesson in ceramics.

We took a tourist train into the Valle

de los ingenios and I climbed

the tower at Manaca Iznaga - a huge structure built a couple of centuries

ago by the local oligarch to keep an eye on his slaves in the fields.

I spent quite a lot of time lying on the sand or my bed or drinking mojitos

or beer and reading the guide book, filling in a little bit of the vast

gaps in my knowledge of the history of the country.

And then I was back in Havana, at the same casa particulare I'd

stayed at before the festival with Jill (who speaks Spanish) and Gilly.

On my own, I was forced to hablar español, and after a week of

having a go in Trinidad I actually managed to communicate with and impress

Alberto, the casa owner. I also managed to get a taxi ride home in a

1959 Chevrolet Impala on my last night, which meant I could leave early

the next morning feeling that I'd had a real Cuban experience.

Back

to top

|